The World Inside an SM57

The Shure SM57 is probably the single most common piece of professional audio equipment in the world. It is used on every kind of sound source, every day, in live music venues everywhere; it has been used on drums and guitar amps in countless recordings; and it has been on the lectern of every US president since Lyndon Johnson. The world uses them with abandon, and as a result they are as common as dirt and almost as cheap, being available for as little as 75 US dollars on Ebay.

What few people realize is that this humble bit of kit embodies a staggering amount of scientific knowledge and technical know-how. Everything about this microphone, from its tailored frequency response, to its ability to work safely in earsplitting high SPL applications, to its durability, small size, light weight, and low price, is a collective result of the disparate knowledge of countless people: electrical engineers, acousticians, materials scientists, machinists and manufacturers. The hours of research implicit in every SM57 are beyond counting.

The SM57 is an example of what is called a 'moving coil' or 'dynamic' microphone. There are, generally speaking, three kinds of microphones in common use: condenser microphones, ribbon microphones, and dynamic microphones. There are other kinds of course, many of which have been designed for very specific purposes, but the vast majority of the microphones used for musical applications such as studio recording or live sound reinforcement belong to one of the three categories listed above.

All three kinds of microphones were first developed in the early years of electrical audio engineering: the condenser microphone was patented by E.C. Wente in 1916;

the ribbon microphone was invented by Walter Schottky in 1923;

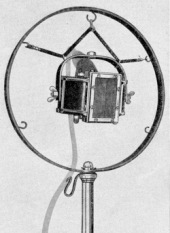

while the first dynamic microphone, initially called the Marconi-Sykes Magnetophone, was put into use by the BBC in the same year.

This Magnetophone thingie was an amazing piece of work. It was known as the 'Meat Safe', because it "required an enormous (6ft x 4ft x 2ft) 10 valve amplifier" to operate. Even more imposing than the amp was the fact that it required an immense electromagnet, consuming 4 amps from an 8 volt battery (pdf), just to create the microphone's internal magnetic field.

Now what we call a dynamic microphone today consists of a diaphragm that vibrates when sound waves hit it, that is attached to a coil of wire that is suspended in a magnetic field. This concept was first developed by E.C. Wente and was awarded US patent #1,766,473 in 1930. Reading this patent, with its description of an 80 year old technological concept, is quite humbling. This passage, describing part of a method of negating the natural resonance of the diaphragm, is typical:

Click for more

To simplify greatly: the device described in this patent works by an action that is analogous to the action of a loudpeaker in reverse. The magnetic energy necessary to make this kind of microphone work is very great considering its size, which is why the commercial development of these microphones lagged behind the development of condenser and ribbon microphones. The only way to get that kind of magnetic force in the 1920's was to use large electromagnets, which were bulky, heavy, and altogether inconvenient.

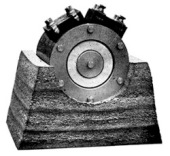

What changed this situation was the development of more powerful permanent magnets. The first of these were developed around 1930 and were made of Alnico (aluminum-nickel-cobalt). Alnico allowed Shure to introduce its Unidyne series of microphones, which were, as the catalog stated (pdf) "The first high quality, low-cost moving-coil type dynamic [microphone] with true cardioid unidirectional characteristics". This might have been true, but the 55A still cost just under 43 US dollars in 1940, which amounts to about 800 dollars in 2019 when adjusted for inflation. This is not a low price for a dynamic microphone in today's market. The direct descendent of the 55A, the 55SH, today lists for just 179 US dollars in 2019. Shure's SM7, a first rate microphone used on hundreds of classic vocal tracks, lists for just 400 dollars. And the humble SM57 bottoms out the list with a MSRP of just 99 dollars, which would have been less than 6 dollars in 1940.

What has caused this drop in price? Well, what hasn't? After the advent of Alnico magnets came the development of barium and strontium based ceramic magnets in the early fifties, samarium-cobalt magnets in the seventies, and neodymium-iron-boron magnets in the early eighties. Each of these developments allowed new levels of performance to be achieved, or allowed the same levels of performance to be achieved more conveniently, or for less money. These magnets have been exploited not just by makers of dynamic microphones, but by makers of loudspeakers, headphones, and phonograph cartridges as well.

Then, too, the other components of these microphones have undergone a similar evolution. The duralumin diaphragm employed by Wente has been replaced many times over, as can be seen by looking over this patent, assigned to, you guessed it, Shure Brothers, in 1993. It cites 7 other patents, one of which describes 'Multiple layer packaging sheet material' of all things. This patent in turn cites about 40 other patents, ranging over a hundred years, which describe things like methods 'for making a polyvinylidene chloride coated biaxially oriented polyethylene terephthalate container'....

Layers and layers of mind-numbingly complex technical and scientific insights, all to explain some packaging material. Packaging material which, apparently, is useful in the manufacture of microphone diaphragms.This ramified repository of knowledge presents itself no matter where you look: magnet, diaphragm, voice coil, voice coil cartridge, methods of assembling voice coil cartridge, materials used in housing of voice coil cartridge...: all reach with a million roots into the knowledge of the past; all are constantly being refined and improved upon.

If you sit back and think about it, the whole thing beggars the imagination: centuries of scientific knowledge; countless man-hours of research and testing; manufacturing procedures taking place at facilities across the globe, using materials from across the globe, to be shipped across the globe. And all of this is taking place just to allow the Rod Torfulson's Armadas of the world to record their demos on a budget. Kinda chokes you up, doesn't it?

Originally posted at http://realmusicmedia.net/verge.html#04_26_2010