:: :: :: :: :: :: :: :: :: :: :: :: ::

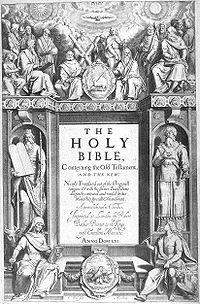

In a flat white box surrounded by acid-free paper, I have a single page from the first edition of the King James Bible. It was a gift from my parents (they know me well). That piece of paper turned 400 years old in May of 2011.

The 1611 Bible is not just one of the great achievements of the English language; it's one of England's great gifts to the world. Building on the achievements of Wycliffe and Tyndale and Coverdale and the Great Bible, the Bishop's Bible, and the Geneva Bible, but significantly different from them at key points, the KJV still reigns supreme. It shapes our language still. Hundreds upon hundreds of translations later, we still go to King James for the 23rd Psalm and the Lord's Prayer.

It'll be worth your time to find and read Adam Nicolson's engaging book God's Secretaries. Nicolson is one of those historians who has become so familiar with the time he's studying that he can see implied statements and pull out their entire meaning for us who are so removed from Jacobean society.

Here are some passages in which he discusses Jamses's kingly vision, reveals some hilarious aspects of Puritan culture (some of which are still with us), and looks at various rules by which the translators will operate. Each rule comes under close scrutiny, with miraculously revealing results.

:: :: :: :: :: :: :: :: :: :: :: :: ::

T he Bible was to become part of the new royal ideology. Elizabeth had portrayed herself as a Protestant champion against the powers of Rome and Spain. That was now out of date. James, Rex Pacifus, was to make the Bible part of the large-scale redefinition of England. It had the potential to become, in the beautiful phrase of the time, an irenicon, a thing of peace, a means by which the divisions of the church, and of the country as a whole, could be encompassed in one unifying fabric founded on the divine authority of the king.

:: :: :: :: :: :: :: :: :: :: :: :: ::

S ome Puritans maintained that the names of the great figures in the scriptures, all of which signify something — Adam meant 'Red Earth', Timothy 'Fear-God' — should be translated. The Geneva Bible, which was an encyclopaedia of Calvinist thought, ... had a list of those meanings at the back and, in imitation of those signifying names, Puritans ... had taken to naming their children after moral qualities. Ben Jonson included characters called Tribulation Wholesome, Zeal-of-the-Land Busy and Win-the-fight Littlewit [in his works], and Bancroft himself had written about the absurdity of calling your children 'The Lord-is-near, More-trial, Reformation, More-fruit, Dust, and many other such-like'.

These were not invented. Puritan children at Warbleton in Sussex, the heartland of the practice, laboured under the names of Eschew-evil, Lament, No-merit, Sorry-for-sin, Learn-wisdom, Faint-not, Give-thanks, and, the most popular, Sin-deny, which was landed on ten children baptised in the parish between 1586 and 1596. One family, the children of the curate Thomas Hely, would have been introduced by their proud father as Much-mercy Hely, Increased Hely, Sin-deny Hely, Fear-not Hely, and sweet little Constance Hely.

Bancroft, and this royal translation of the Bible, could give no credit to that half-mad denial of tradition. It was one that travelled to America with the Pilgrim Fathers. Among William Brewster's own children, landing at Plymouth Rock, were Fear, Love, Patience, and Wrestling.

:: :: :: :: :: :: :: :: :: :: :: :: ::

[R ule 6:] Noe marginal notes att all to be affixed, but only for ye explanation of ye Hebrew or Greeke Words, which cannot without some circumlocution soe breifly and fitly be expressed in ye Text.

There were to be no marginal notes 'att all', not even those which might conform to the ideology of the established Jacobean church. The text, as all good Protestants might require, was to be presented clean and sufficient of itself, except where the actual words of the original were so opaque that a 'circumlocution' might not explain them within the text. 'Circumlocution' did not mean then quite what it means now. Thomas Wilson in The arte of rhetorique, published in 1553 and in use throughout the sixteenth century, had described circumlocution as 'a large description either to sett forth a thyng more gorgeouslie, or else to hyde it'. The words of this translation, then, could embrace both gorgeousness and ambiguity, did not have to settle into a single doctrinal mode but could embrace different meanings, either within the text itself or in the margins. This is the heart of the new Bible as an irenicon, an organism that absorbed and integrated difference, that included ambiguity and by doing so established peace. It is the central mechanism of the translation, one of immense lexical subtlety, a deliberate carrying of multiple meanings beneath the surface of a single text. This single rule lies behind the feeling which the King James Bible has always given its readers that the words are somehow extraordinarily freighted, with a richness which few other texts have ever equalled. Again and again, the Jacobean Translators chose a word not for its clarified straightforwardness (which had been Tyndale's focus in the 1520s and '30s, and the Geneva Calvinists' in the 1550s) but for its richness, its suggestiveness, its harmonic resonances. That is the heart of the irenicon: divergence held within a singularity, James's Arcadian vision made word.

:: :: :: :: :: :: :: :: :: :: :: :: ::

E verything in the modern frame of mind, trained up on centuries of individualism, and on the overriding importance of individual freedoms, rebels against the idea. Joint committees know nothing of genius. They do not produce works of art. It is surely lonely martyrs who struggle for unacknowledged truths. Committees thrive on compromise and compromise produces fudge and muddle. Isn't the beautiful, we now think, to be identified with what is original, the previously unsaid, the unique vision of the individual mind? How can a joint enterprise of this sort produce anything valuable? There may be one or two modern examples of successful co-operative writing — Pound and Eliot, perhaps Auden and Isherwood — but the idea of a committee producing a work of genius? That today sounds like a joke.

Not in 1604. If you think of the King James Bible as the greatest creation of seventeenth-century England, a culture drenched in the word rather than the image, it is easy to see it as England's equivalent of the great baroque cathedral it never built, an enormous and magnificent verbal artifice, its huge structures embracing all 4 million Englishmen, its orderliness and richness a kind of national shrine built only of words.

:: :: :: :: :: :: :: :: :: :: :: :: ::

[L ancelot Andrewes had] a daily habit of self-mortification and ritualised unworthiness in front of an all-powerful God, a frame of mind which nowadays might be thought almost mad, or certainly in need of counselling or therapy. But that was indeed the habit of the chief and guiding Translator of the King James Bible: 'For me, O Lord, sinning and not repenting, and so utterly unworthy, it were more becoming to lie prostrate before Thee and with weeping and groaning to ask pardon for my sins, than with polluted mouth to praise Thee.'

This was the man who was acknowledged as the greatest preacher of the age, who tended in great detail to the school-children in his care, who, endlessly busy as he was, would nevertheless wait in the transepts of Old St Paul's for any Londoner in need of solace or advice, who was the most brilliant man in the English Church, destined for all but the highest office.... But alone every day he acknowledged little but his wickedness and his weakness. The man was a library, the repository of sixteen centuries of Christian culture, he could speak fifteen modern languages and six ancient, but the heart and bulk of his existence was his sense of himself as a worm. Against an all-knowing, all-powerful, and irresistible God, all he saw was an ignorant, weak, and irresolute self. ...

How does such humility sit alongside such grandeur? It is a yoking together of opposites which seems nearly impossible to the modern mind. People like Lancelot Andrewes no longer exist. But the presence in one man of what seem to be such divergent qualities is precisely the key to the age. It is because people like Lancelot Andrewes flourished in the first decade of the seventeenth century — and do not now — that the greatest translation of the Bible could be made then, and cannot now.